Sonic Rupture, a means for introducing sounds into urban spaces

Interview with Jordan Lacey, a sound artist, thinker and occasional provocateur, who spends much of his time imagining new ways societies might relate with their cities.

LxD: Thank you for very much for agreeing to take part in this interview. Could you please introduce yourself to the reader with a short listening focused outline of you and your work.

Jordan Lacey is a Vice-Chancellor's Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Architecture & Design at RMIT University. His research is located at the interface of the sonic arts and urban design, investigating the role of sound installations in the development of creative cities and improved social health and wellbeing. He is presently managing several industry-based projects, each exploring the potentialities of weaving new listening experiences into everyday life. Jordan is author of the book Sonic Rupture: a practice-led approach to urban soundscape design (Bloomsbury 2016).

Notating traffic sound - listening to and notating sound wall traffic (conducted as part of Transurban Innovation Grant, exploring the possibilities of soundscape design systems to manage roadside traffic noise).

LxD: What does listening mean for you?

Listening equals connection. Listening means to stop, tune in. Forget the body. Feel your being merge with sounds that touch, caress your body. Feeling free to be transported. It is a type of meditation, but not in any robust disciplinary sense. But more a letting go of preconception and feeling your way into another state of being. I was very interested to learn that Aboriginal Australia has a long deep listening practice. And I’m sure we can extend this statement to other First Nations. The Dreamings of Aboriginal Australia (which as an uninitiated person I can never understand) strikes me as a place of being that was imagined through a deep tuning into the environment. Are these discoveries that were made, or realities that were dreamt? I don’t know. But I suspect that these deep listening practices revealed to them mysteries, in many cases, now lost by European invasion. I wonder to myself, could such listening practices, in the present, help us rebirth our cities – to transform them from functional places in to dreaming places? Where the possible imaginary scope of existence expands? Listening means trusting the senses. To reveal mysteries that may not be immediately accessible to the deterministic mind.

'You don't go Nowhere else' - sound recordings as part of Mildura art gallery exhibited piece related to Barkindji people's relationship to land in NW Victoria. Voice, Uncle Barry, an elder of the Barkindji nation. Interview kindly provided as part of Interpretive Wonderings workshop.

LxD: In what way does your work, research or practice involve listening?

I listen everyday. It’s a way to be free of the functional demands of everyday life. Sometimes on the train, with the crowds of fellow passengers, I hear the spits, hisses and cries of the train. I think, the train is alive. Why not? But my focus, as a sound artist working in the field of urban design is to wonder how I can intervene in daily life to create installations, or moments, that induce deep listening. However, anything I put into the urban is essentially non-existent until someone stops to listen thereby allowing his or her imaginary response to dream the environment. The sounds I help put into place are in one sense completely useless – no ‘use-value’. They have no function. But they can find their way into an imagination should the listener desire it.

LxD: What is it you hear in your work and research?

I hear possibility. Salomé Voegelin in her recent book, Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound (Bloomsbury, 2014) talks of the possible in listening – I agree! That listening makes the impossible possible. Dreams are impossible. In my research it is my desire to create places that become meaningful, completely outside of the bureaucratic, functionalist networks that drive our civilisation. Access points reminding us that being human is more than utilitarian, that there is more than the human – a vaster interconnective network. But I have no expectation once a sound finds its home in a space. It’s up to the listener then.

'Noise Meditations' - sound piece for national Gallery of Victoria (NGV). All sounds derived form air-cons, train platform and voice.

LxD: Do you listen out for something particular, do you work with a pre-given set of auditory expectations and aims, or do you start defining aims from what you hear?

I listen to a space as if it were alive, wherever it is. Consider me a pantheist. Everything is alive, not in the sense of human life but in the sense of its capacity to express – its shimmering vibratory unfolding. When I connect with a space, as I get to know it, it becomes place. Upon this transformation I dream the sounds as something new. The introduced sounds, for me, must be born in the space: an upwelling. There is no prescription. In my book, Sonic Rupture: A Practice-led approach to Urban Soundscape Design (Bloomsbury, 2016), I put forward the notion that the role of sound art in urban design is to create distinct locations in which everyday sounds are transformed into new listening experiences. For those that find the locations, the sounds might weave new ways of knowing. It’s like finding a special place in nature that somehow feels unique, a spot for you. If we can create this in the city, somehow – we have a rupture point.

LxD: How do you engage your audience/ readers in those aims? How do you want them to listen and what do you want them to hear?

I have no preconception. Only that we all have the capacity to listen, or at least to feel sound. To let go of preconception and allow the imagination to do its work. The imagination is not merely a plaything to me – the abode of happy children. It is a real and tangible way to relate to existence and express one’s unique self. I like to think that the dreamings of the First Nations was the birth of the known world, as accessed through the imagination. This process needn’t stop. Relearning the power of listening is part of this continuing unfolding.

LxD: Does the auditory material you produce contribute to a scientific or an artistic knowledge?

Probably not. Maybe an artistic knowledge. Certainly in my book, Sonic Rupture, I make a case for artistic practice as a means for introducing sounds into urban spaces. That is, the placement of sound in our cities should unfold from a thoughtful and iterative practice. I hope that the auditory material I have provided in conjunction with my book will help provide a sense of the value of artistic research. But of course, all artistic practice is unique. Each artist will find a different unfolding. I think science has dominated sound long enough with its deterministic language of acoustics. Time to let the imagination shape sounds into richer human encounters. But I’m not anti-science! I work with engineers and scientists in collaborative projects. I’m simply saying that artistic practice must become an equal part of the conversation. I am excited to read for example that Prof Marcel Cobussen will be delivering a lecture on the importance of artistic practice in the design and planning of public environments (part of The Role and Position of Sounds and Sounding Arts in Public Urban Environments, conference 29/30 November.) In my mind, these types of happenings demonstrate that there is a growing awareness that art is just as important as design, engineering, planning etc, when considering the development of our cities.

'Invisible Infrastructures' - sound file of sound art installation, vibrating containers and playing back site-specific sounds (with Eliot Palmer, Fiona Hillary and Shanti Sumartojo).

LxD: Could you describe the listening methodology, tools, technology, approaches, etc. you employ –how do you listen?

Soundwalking. Stop and absorb. Ambisonic and hypercardioid recordings. Anywhere anytime, let the sounds enter the ears. Don’t control them. Let them be. Allowing your internal world to entrain, and be shaped. That’s all.

LxD: Do you use sound as a qualitative or a quantitative data: e.g. do you analyse the auditory material itself, your listening and the heard, or do you deal with its presentation as spectrogram, dB, etc.? And do you make aesthetic or scientific decisions in how you use this material?

I am working on a project at the moment dealing with creative ways to respond to roadside noise (Transurban Innovation Grant). It’s a collaboration between engineers and artists. It has been really interesting, and challenging, because what is clear is that engineers measure and artists listen. So when we came up with a result that no one could hear, the engineers weren’t concerned. If they can see a difference in their measuring equipment, there is change! But of course the artists and designers in the group are like, hey we need to hear something! So, although I enjoy using specific analytical tools like spectrograms and SPL meters as part of my practice, from an experiential perspective if you can’t perceive a change then what’s the point? Interestingly, I think this is at the heart of emerging approaches to urban sound design. The idea that measuring equipment is the guiding principle because it can be trusted, is slowly being replaced with a perceptual perspective. We must know the human impact to truly know the difference.

Vibrating Sheds - testing vibrational transduction in the back shed, as part of City of Casey funded research project exploring possible relationships between sound and placemaking.

LxD: Do you combine the heard, the auditory information gained with other materials, images, numerical data etc. in the process of analyses and evaluation?

To an extent. In my book I have over 30 audio samples of my sound installations working in space. This is great sample material for thinking about how sound can blend with space. Of course, recordings are always inferior to the feeling of space itself. I have also collected over 50 images of my works to try and give a sense of place. As part of the artistic research practice, for us to be taken seriously, documentation and an attempt to somehow systemise that documentation into a robust argument is critical. It has served me well so far. I am presently working on three industry funded research projects exploring the possible impacts of sound-based works in public spaces. I think presenting myself as an artistic researcher with a serious interest in responding to social problems has helped this process. So, for me, combining the heard with other media serves a purpose – to help push through new ways of thinking.

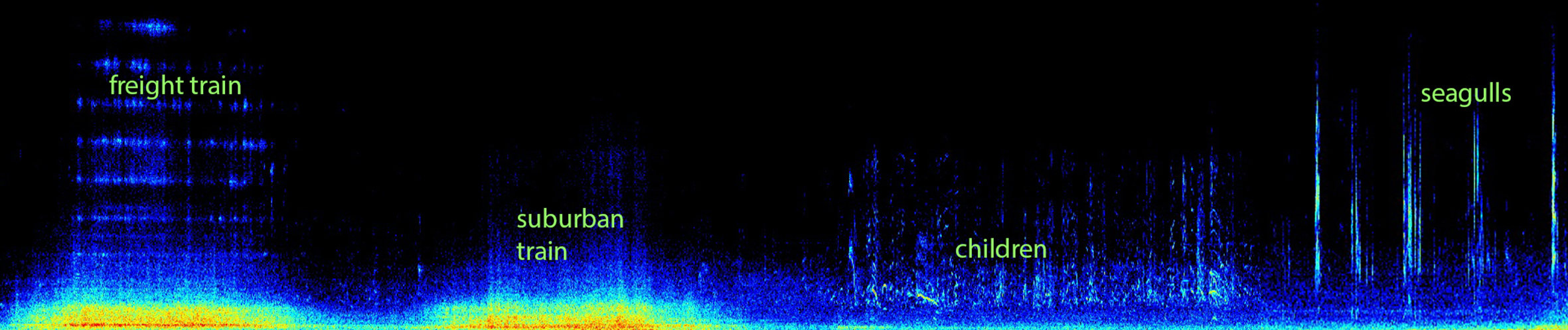

Sounding Batman Park - sonogram - sonogram of field recording (with Catherine Clover, COM Test Sites).

LxD: How do you think sound and listening can contribute to the understanding and responding to current, socio-political, geographical and ecological issues?

My view on this is tangential. I don’t think we as sound artists can actually make any direct changes. These are direct political questions that require active engagement. Climate change won’t be solved by an artist writing a piece of music, or creating an installation about it. It requires the shutting down of coal mines, the rise of the Greens etc. However, what I do think is, is that art, and particularly sound art, has the capacity to directly engage the imagination as a real and transformative agent. To remind us that the world is more than profit and infrastructure development agendas. That deep relationships with a living world are equally important for the future of humanity. Thus, sound and listening can contribute to a shifting consciousness about the value of the world. That is something, I guess. From the perspective of urban design, creating listening spaces that encourage people to stop, listen and engage could be just enough to remind us that we are not just expressions of the city’s hectic pace, but something more. That is the point of the sonic rupture: to rupture perception, allowing new perspectives to emerge.

LxD: Could you refer us to any reference texts, works, or other material that you would like to tell the reader about for our reference section?

Well obviously there is my book Sonic Rupture: a practice-led approach to urban soundscape design (Bloomsbury 2016), and a recent article I wrote about sound art installations titled ‘Sonic Placemaking: ten attributes and three approaches for the creation of enduring urban sound art installations’ (Organised Sound 2016). However, I would also encourage readers towards texts by Jean-Paul Thibaud, Marcel Cobussen, Gascia Ouzounian, Salomé Voegelin and Brandon LaBelle; all of whom are exploring the notion of sound in public space and the possibilities afforded by the intelligent and skilful introduction of sounds into public environments. Certainly look out for proceedings related to the approaching ‘Conference on The Role and Position of Sounds and Sounding Arts in Public Spaces’ convened by Prof Marcel Cobussen.

LxD: Do you have any terms you might want to contribute to our growing glossary on listening terminology?

Sonic Rupture – a point in space where the systemized signs of everyday life, are momentarily dispersed for the upwelling of imaginative possibility.

Jordan Lacey – Field Recording (Interpretive Wonderings Workshop).